Steinbach, Manitoba

Steinbach | |

|---|---|

| City of Steinbach | |

Clockwise from top: The Steinbach Millennium Clock Tower in downtown Steinbach, the historic Stony Brook and the Steinbach Post Office. | |

| Nickname: The Automobile City | |

| Motto: "It's Worth the Trip" | |

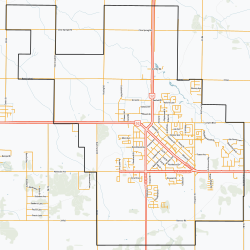

City boundaries | |

| Coordinates: 49°31′33″N 96°41′02″W / 49.52583°N 96.68389°W[1] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Manitoba |

| Region | Eastman |

| Established | 1874 |

| Incorporated | 1946 (town) 1997 (city) |

| Government | |

| • City mayor | Earl Funk |

| • Governing body | Steinbach City Council |

| • MP (Provencher) | Ted Falk (CPC) |

| • MLA (Steinbach) | Kelvin Goertzen (PC) |

| Area | |

• City | 37.56 km2 (14.50 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 37.56 km2 (14.50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 253.6 m (832 ft) |

| Population (2021)[2] | |

• City | 17,806 (3rd) |

| • Density | 474.1/km2 (1,228/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 17,806 (126th) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Forward sortation area | |

| Area code(s) | 204, 431, 584 |

| Demonym | Steinbacher |

| Website | City of Steinbach |

Steinbach (/ˈstaɪnbæk/ ) is the third-largest city in the province of Manitoba, Canada, and with a population of 17,806, the largest community in the Eastman region.[3] The city, located about 58 km (36 mi) southeast of the provincial capital of Winnipeg, is bordered by the Rural Municipality of Hanover to the north, west, and south, and the Rural Municipality of La Broquerie to the east. Steinbach was first settled by Plautdietsch-speaking Mennonites from Ukraine in 1874, whose descendants continue to have a significant presence in the city today.[4] Steinbach is found on the eastern edge of the Canadian Prairies, while Sandilands Provincial Forest is a short distance east of the city.

Steinbach's economy has traditionally been focused around agriculture; however, as the regional economic hub of southeastern Manitoba, Steinbach now has a trading area population of about 50,000 people and significant employment in the financial services industry, automobile sales, tourism, retail, and manufacturing.[5] The city had a population growth of 11.1% between 2016 and 2021[6] and has gained national recognition as an immigration destination of Canada and a model for immigrant integration in the country.[7]

Etymology

[edit]Steinbach means "Stony Brook" in German.[8] Steinbach's stony brook was drained sometime after settlement. Low German-Mennonites named the town Steinbach in 1874, after a village also called Steinbach in Borosenko colony, Ukraine.[8]

History

[edit]Treaty 1 and the East Reserve

[edit]After the Assiniboine and Cree First Nations left the region in the 1820s, the Anishinabe hunted in and moved seasonally through the area on their way to the burial grounds in the Whiteshell.[9][10] A bison trail ran alongside the Steinbach Creek on the far eastern edge of the Canadian prairies, a trail that was used by First Nations people for a number of years after settlement.[9] In 1871, the Imperial Crown of Great Britain and Ireland and Anishinabe people signed Treaty 1, after which time the Canadian government began recruiting European farmers to the region, establishing the English and Scottish settlement of Clear Springs in 1872, just north of the present day location of Steinbach, and partially contained within the modern city limits.[10] At the time of English and Scottish settlement, the nearest settled area was 17 km north in Ste. Anne, Manitoba, a Métis village founded 17 years earlier in 1856.

In 1873, the Canadian government sent William Hespeler to recruit Mennonites to move to the area. By the 1870s, some Plautdietsch-speaking Mennonites in Ukraine became dissatisfied with increasing Russification and the removal of their military exemption and were persuaded by Hespeler to investigate Manitoba as a possibility for relocation. These Mennonite communities were not ethnically Russian, but had Dutch ancestry dating back to 16th century Friesland and Flanders, after which time they lived in Prussia for two centuries and then the Russian Empire where they became known as Russian Mennonites, a misnomer given that they were ethnically Dutch.[11]

In 1873, the Mennonites sent delegates to North America to investigate and negotiate terms of immigration. After touring a number of locations in North America, many of the delegates decided to move their people to Kansas, however, the more conservative groups were persuaded to settle in the new Canadian province of Manitoba, because the Canadian government was more generous in their guarantees of religious freedom. In 1873, a Privilegium was signed between the Mennonite delegates and the Canadian government, and a year later Mennonites started to arrive in the region. The document guaranteed, among other things, military exemption, freedom of religion, private schools, and land, known as the East Reserve.[12] In the year following the signing of the Privilegium, Mennonites from the Bergthaler and Kleine Gemeinde groups immigrated to Manitoba, aided by Ontario Mennonite Jacob Yost Shantz, and founded dozens of villages in the East Reserve.

Early history (1874–1909)

[edit]

Steinbach's original 18 Mennonite settler families were almost entirely of the new Kleine Gemeinde sect of Mennonites, a small conservative minority known for being gifted farmers. They left the Borosenko colony (a newly-formed offshoot of the larger Molotschna (or Milk River) colony) in Ukraine and arrived in Canada late in the summer of 1874.[11]

Aided by their Métis neighbours, the families disembarked on the far west side of the reserve at the forks of the Rat and Red Rivers, near present-day Niverville. As they moved east across the reserve, they found that much of the better land in the reserve had already been settled a few months earlier by the Bergthaler and earlier Kleine Gemeinde families. The earlier settlers had come to realize the area suffered from excessive moisture and settled upon much of the higher lands and gravel ridges.[11] Steinbach's settlers chose the best land that was available to them, which was in the very northeast corner of the East Reserve. The 20 homesteads were laid out on the northeast side of present-day Main Street along the creek, where they founded the village of Steinbach, taking the name "Steinbach" from the village where they lived in Borosenko.[11]

Contrary to the preferences of the Canadian government, the early settlers of Steinbach, like other Mennonite villages, organized the village into a Strassendorf, or street village, with each family occupying a long narrow strip known as a Wirtschaft.[8] In the first year they built temporary shelters known as semlin, before building more permanent housebarns. Most of the settlers were farmers, but in a somewhat urban setting, and lived, to some degree, communally, and shared a common pasture at the end of the village. They started a school in the first year, and in the following year of 1875 built a school and teacherage.[11] Steinbach's Main Street was hacked out of thick poplar bush along the creek, where a bison trail ran, a trail that was still used by Indigenous people during Steinbach's early years.[9]

In June 1875, Steinbach's spiritual leader Rev. Jakob Barkman, who had led the Kleine Gemeinde to Canada, drowned in the Red River, along with Jakob K. Friesen on a trip to Winnipeg for supplies.[13] This left the community without religious leadership for some time.

After a plague of grasshoppers destroyed the crops in 1876, residents of Steinbach met in Blumenort to discuss the possibility of migrating to Minnesota or Nebraska. However, 60-year-old matriarch Elizabeth Rempel Reimer persuaded the group to stay in Steinbach, a stirring and historically significant speech which signified the important role of women in the community and resulted in Steinbach's continued survival as a community, unlike dozens of other East Reserve villages which have since disappeared.[8]

In 1877, Lord Dufferin toured Manitoba's new Mennonite settlements and stopped just west of Steinbach where he could see "half a dozen villages" in the distance. A crowd of 1000 people greeted his arrival.[8] That same year, the first windmill in the town was built by Abraham S. Friesen.[14]

The death of Rev. Barkman left Steinbach without religious leadership for a number of years, creating a vacuum that made the villagers receptive to John Holdeman when he visited in 1881. After Holdeman's visit, many locals from the Kleine Gemeinde joined his new church, Church of God in Christ, Mennonite. This was the first of many schisms and revivals in Steinbach and eventually the town would be known for having dozens of churches, many of them different variations of Mennonite, a dynamic that has shaped the city's character.[8] After a period of eight years, in 1882, Mayor Gerhard Giesbrecht said that the village had grown to 28 families with a population of 128.[11]

Various epidemics swept the area in the late 1800s, including scarlet fever, whooping cough, and diphtheria. In the spring of 1884 alone, more than seventy people died, mostly children. Another whooping cough epidemic took place in 1900.[9]

By 1900, the settlers had drained the swamps and cleared the land making it more suitable for the farming of wheat, barley, oats and potatoes. In the 1901 census, Steinbach had a population of 366, and almost the entire population still spoke Plautdietsch, with only a few reporting a knowledge of English.[9]

End of the Strassendorf (1910–1945)

[edit]In 1910, the street village linear settlement, or Strassendorf (Straßendorf in German) for the community ended.[8] Prior to this time, the settlers of Steinbach lived in long narrow strips, called Wirtschaft (plural: Wirtschaften), along the Steinbach Creek. Following the lead of the neighbouring Mennonite village of Blumenort, who had abandoned their Strassendorf system a year earlier, the village of Steinbach was surveyed and land was redistributed with individual titles to open-field properties. Those who were given inferior land were financially compensated by the others. Although a communal pasture for cattle was maintained for some decades after this, the end of the linear settlement meant the end of the traditional communal lifestyle of the Mennonites in this area, but also opened the area up to greater entrepreneurial enterprise.[11] The mayor, or schulz, of Steinbach at this time was Johan G. Barkman, Steinbach's longest serving schulz, who held that position for twenty-five years, including overseeing such significant events as the end of the Strassendorf.[15] In 1911, the Kleine Gemeinde church, who had met in the village school up until this point, constructed a building on the south end of the village.[9]

In 1912, J.R. Friesen opened a Ford auto dealership in town, which was the first Ford dealership in Western Canada. At the time, Friesen was excommunicated from the Kleine Gemeinde for adopting the modern technology, but within a few years, many Steinbachers accepted the automobile as an acceptable mode of transportation.[11]

By this time, Steinbach had a third Mennonite church, the Bruderthaler, who, unlike the Kleine Gemeinde and Holdeman Mennonites, taught that being successful in business was not a sin and, in fact, was to be encouraged. The new theology moved Steinbach from a more traditional and agriculturally-based economy to one that emphasized business and industry.[16] Entrepreneurs took advantage of the business opportunities at the time and several small businesses sprang up. Many other important and large businesses developed as well, helping to establish Steinbach as a regional service centre for the area.

By 1915, Steinbach had grown to a population of 463 and continued to attract immigrants from Europe.[11] Many of the new immigrants were Bergthaler Mennonites, but Steinbach also was the destination for new German and Lutheran settlers, as well as some British families who had previously settled in the Clearspring Settlement slightly to the north.[11] Steinbach's first bank, the Royal Bank, opened in 1915.[9]

During World War I, most Steinbach Mennonites were given an exemption from military service, as promised in the Privilegium they had agreed to upon immigration in the 1870s.[8] Mistakenly considered "ethnic Germans", even though they were actually primarily of Dutch ancestry, the Mennonites were caught up in the anti-German sentiment of the time and Conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden banned Mennonites from Steinbach and other areas from voting in 1917.[8]

A year later, in 1918, as soldiers returned to North America, Spanish flu struck the village, killing many. Mennonites in the region were particularly affected by the outbreak, dying at a rate nearly twice that of other ethnic groups.[17][18]

After the First World War, Borden banned Mennonites and other pacifists from immigrating to Canada.[8] The ban lasted for three years, from 1919 to 1922, when the new Liberal government lifted the ban. At the same time, there was the out-migration of the more conservative Mennonites, who left the area for Mexico and Paraguay, after the Canadian government required them to learn English and attend public schools, issues which seemed to be in violation of the Privilegium signed in 1873.[12]

In 1920, the village of Steinbach was formed into an "Unincorporated Village District" of the Rural Municipality of Hanover.[15]

After the Mennonite immigration ban was lifted in 1922 by Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, a second wave of Mennonite immigration occurred due to the Russian Revolution, and many of the "Russlander" Mennonites took over farms and land left unoccupied by the Mennonites leaving for Latin America. During the 1920s, thousands of Mennonite refugees fled the Soviet Union, many of them arriving in the Steinbach area.[19] Moscow Road, which had been pejoratively named to refer to the Russlander Mennonites who lived there, was later renamed McKenzie Avenue after the Prime Minister who had allowed them to come to Canada as refugees.[20]

In 1931, local man Abraham Loewen founded the Loewen Funeral Chapel, the first funeral home in southeastern Manitoba, which decades later was taken over by his son Ray Loewen, who built the company into the Loewen Funeral Group, before its eventual downfall as depicted in the 2023 film The Burial.[21]

In 1941, the Steinbach Credit Union opened, partially in response to the difficulty in obtaining loans from the larger banks.[8]

During World War II, most Steinbachers who were eligible for the draft served in alternative service as conscientious objectors, though some also served in the active military.[8] After the war, a third major wave of immigration boosted Steinbach's population, with thousands of Mennonites again fleeing Europe.[19]

Incorporation as a town (1946–1996)

[edit]Steinbach was incorporated as a town on 31 December 1946, with the Main Street being paved the following year.[22][8] The new town elected Klaas Barkman as mayor who, along with councillor and auto-dealer A.D. Penner, had been instrumental in Steinbach's incorporation.[23] As the regional service centre for the area, Steinbach developed manufacturing, trucking, and retailing, particularly in automobile sales. Steinbach became known regionally as the "Automobile City", a name coined by A.D. Penner.[8]

From the 1940s to the 1960s, T.G. Smith, was a local bank manager who organized many of Steinbach's first recreational activities, which the Mennonite population had been reluctant to adopt on their own.[23]

In 1958, Leonard Barkman was elected mayor and served until 1970.[23] Barkman, a member of the Liberal Party, also served as M.L.A. while mayor of Steinbach, a once common practice that is no longer permitted in Manitoba. Barkman was the first Mennonite from the area, who had previously eschewed this level of political involvement, to join the Manitoba Legislature.[23]

During the 1950s and 1960s, Steinbach was home to many Christian revival meetings, including frequent visits by George Brunk, Ben D. Reimer and others. These meetings were held in a quonset just off of Main Street called The Tabernacle.[8] The new more evangelical theology transformed the doctrine and practices of many of the local Mennonite churches and contributed to their assimilation. Many local churches adopted evangelical theology or merged it with their traditional Anabaptist theology, and some dropped the Mennonite label altogether.[24]

In 1960, the Kleine Gemeinde church building, which by then was called the Evangelical Mennonite Conference, burned to the ground. The same year, the last traditional Mennonite housebarn in Steinbach was torn down by A.D. Penner.[23] Partially in response to the destruction of heritage buildings in the area, such as the historic housebarn destroyed by A.D. Penner, residents in the 1960s saw the need to preserve and remember the Mennonite history of the region. In 1967, the Mennonite Heritage Village museum in Steinbach was opened.[8]

In 1966, infamous gold thief Ken Leishman escaped from Headingly Jail and stole an airplane from Steinbach, solidifying his nickname as the "Flying Bandit".[25]

In 1970, the year of Manitoba's centennial, Steinbach was visited by Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Charles.[23] A crowd of 10,000 waited along the streets of Steinbach as the royals visited, coming from the east along Highway 52 after their visit to La Brouqerie. The Carillon described the visit saying, "it was the most memorable and exciting moment in the history of the Southeast. For the first time since the earliest European settlers arrived in the 1860s and 1870s, a member of the British royal family paid a personal visit to the communities of La Broquerie, Steinbach, Sarto, Grunthal and St. Pierre. For these communities and their people the visit by Queen Elizabeth and Prince Charles on the eve of Manitoba's 100th birthday highlighted a century of economic and cultural development."[23]

In 1972, Jake Epp, a former local high school teacher, was elected Member of Parliament in the region, the first Mennonite in the area to do so. Epp was also the first Mennonite to serve as a federal cabinet minister and was MP until 1993.[26]

In May 1980, Steinbach's first shopping mall, Clearspring Centre, opened on the north end of the community. The mall was named after the historic English and Scottish settlement in the area.[27]

In fall of 1982, Steinbach drew considerable attention after the school board cancelled a scheduled rock concert in the local high school by Queen City Kids.[28] Hundreds of students staged a protest as a result of the cancellation. The incident was alluded to years later in the work of novelist Miriam Toews.[29]

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Aussiedler Mennonites, who had remained in the Soviet Union (particularly Siberia and Kazakhstan) throughout much of the 20th century, or who had resettled in Germany during the 1970s, began to immigrate to the area and continued to do so through the 1990s and early 2000s. Some of these people had converted to the Baptist church during the decades in the Soviet Union.[30] Over all, Steinbach's growth slowed somewhat during the 1980s and early 1990s in comparison to the rate of growth in decades before or since.[31]

In 1996, Les Magnusson was elected mayor of Steinbach, the first non-ethnic Mennonite to hold that position. Magnusson was a vocal opponent of attempts in Steinbach to allow liquor sales.[32]

Contemporary era (1997–present)

[edit]With Les Magnusson as mayor, Steinbach was incorporated as a city on 10 October 1997.[22] In 2000, the windmill at the Mennonite Heritage Village, a recognized symbol of the city, was destroyed by arsonists.[33] It was rebuilt less than a year later with the assistance of Dutch millwrights.[34]

Steinbach attracted prominent attention in 2004 when Mennonite author Miriam Toews, who was born and grew up in Steinbach, published her novel A Complicated Kindness. The book became a bestseller, exploring a fictionalized town modelled after Steinbach. It won the 2004 Governor General's Award for Fiction,[35] and was selected as the 2006 book for Canada Reads, the first book by a female writer to be chosen.[36]

Steinbach continued to grow during Magnusson's tenure and, after the election of Chris Goertzen as mayor in 2006, became one of the fastest-growing cities in Canada.[31] In 2011, Steinbach was officially announced as Manitoba's third-largest city, with the release of the population data from the 2011 Canadian Census. The growth was attributed to immigration from such countries as Germany, Russia, and the Philippines.[37] Steinbach gained national recognition from such newspapers as The Globe and Mail, which described the city as an immigration "hotbed" of Canada and a model for immigrant integration.[7][38]

During March 2013, the city gained national attention when several community members, such as the Southland Community Church and Steinbach Christian High School expressed opposition to provincial Bill 18, an anti-bullying bill that would require the accommodation of gay-straight alliance groups in schools, including faith-based private schools.[39] On 13 September 2013, Bill 18 passed without amendments.[40] Partially in response to this issue, the city's first Steinbach Pride parade was held in 2016. While initially expecting about 200 people, approximately 3,000 people attended the event. This was brought about in part by the fact that not a single elected official from the area attended or endorsed the event.[41][42][43][44]

Ongoing rapid growth meant that the city needed more land and space in order to sustain itself. This led the city to negotiate an annexation of 11 km2 (2,800 acres) from the Rural Municipality of Hanover in 2015, the first major annexation for the city since 1979.[45] Steinbach was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in August 2020, with the virus affecting community members, several businesses, and eventually an outbreak at Bethesda Place, the personal care home at Bethesda Regional Health Centre.[46][47] By November 2020, Steinbach briefly had the highest per capita rate of Covid infections in Canada.[48] The Bethesda Regional Health Centre was reportedly overwhelmed and out of beds on November 13, 2020, with patients having to be triaged in their cars.[49][50]

Beginning in the 2020s, Steinbach became significantly more multicultural with 21% of the population being immigrants, many from The Philippines, India, and Nigeria.[51]

Liquor and cannabis licence referendums

[edit]Despite being prohibited by local churches, Steinbach had alcohol sales, including beverage rooms, throughout the early 20th century. In 1950, however, Steinbach citizens voted to prohibit all liquor sales in the community, although a drinking establishment on Main Street called The Tourist Hotel was allowed to remain, until it closed in 1973.[52]

Since the 1970s, Steinbach has had seven separate referendums on whether liquor sales should be allowed within the confines of the city, all of which failed until a 2003 referendum when Steinbach residents narrowly voted to allow limited liquor sales in the city, despite opposition from then mayor Les Magnusson.[32] The 2003 referendum, however, passed only a dining room licence, permitting alcohol to be sold and served only with sales of food. In 2007, the issue of serving alcohol in restaurant lounges was defeated by only nine votes, while the sale of alcohol at sports facilities such as the Steinbach Fly-In Golf Course was approved.[53] In February 2008, Steinbach Council voted in favour of opening a liquor store in the city.[54] Eventually, the first Liquor Mart in Steinbach opened in March 2009, on PTH 12 North, operated by the Manitoba Liquor Control Commission.[55] The most recent public vote was held in October 2011.[52][56] In this referendum, voters agreed to accept, by a large margin, the following three licences: beverage rooms, cocktail lounges, and private club licences.[57][58]

In 2018, after the Canadian government legalized cannabis, Steinbach residents voted to deny the licensing of retail cannabis stores in the city.[59]

Geography

[edit]Steinbach is located on the eastern edge of the Canadian Prairies, and is also located directly east of the Red River Valley. The flat land in Steinbach was originally a thick patch of poplar trees. The land was flat and very swampy, with the last of the swamps finally drained in 1900, which made the soil more arable and suitable for agriculture. Steinbach's main geographic feature is the Steinbach Creek, which is now mostly dry, still runs along Elmdale Street.[60] Due to higher levels of precipitation received than in the areas of western Manitoba, the natural prairie near Steinbach is defined as tallgrass prairie. Some of this original prairie can still be viewed at the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve south of the city near Vita. The areas to the west and north of Steinbach are defined as flat tallgrass prairie, and part of the Lake Manitoba Plain. The areas south and west of the city progress steadily into treed aspen parkland, eventually growing into Sandilands Provincial Forest and the large boreal forest region extending east and north of the city.

Steinbach is close to many Canadian Shield lakes, such as those located in Whiteshell Provincial Park and the Lake of the Woods in Kenora. Lake Winnipeg (the Earth's 11th largest freshwater lake) is located north of the city.[61] Although no rivers flow through Steinbach, the city is sandwiched by the Seine River to the north and the Rat River to the south. Both are tributaries of the Red River, which flows into Lake Winnipeg.

Under the Köppen climate classification Steinbach has a warm summer continental climate (Dfb).[62] The highest ever recorded temperature in Steinbach was 37.5 °C (99.5 °F) on August 10, 1988, while the lowest ever recorded temperature was −43.5 °C (−46.3 °F) on February 2, 1996.[63] The warmest month on average is July, while the coldest month on average is January. The average annual precipitation in Steinbach is 580.5 mm (22.85 in), with June being the month with highest average precipitation.[63]

| Climate data for Steinbach 1981-2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

35.5 (95.9) |

31.5 (88.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −11.1 (12.0) |

−7 (19) |

0.0 (32.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −16.6 (2.1) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −22 (−8) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −42.2 (−44.0) |

−43.5 (−46.3) |

−37.2 (−35.0) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−2 (28) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−21 (−6) |

−36 (−33) |

−40 (−40) |

−43.5 (−46.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 22.2 (0.87) |

14.5 (0.57) |

21.5 (0.85) |

30.9 (1.22) |

69.2 (2.72) |

100.1 (3.94) |

93.2 (3.67) |

73.8 (2.91) |

57.0 (2.24) |

45.9 (1.81) |

28.1 (1.11) |

24.2 (0.95) |

580.5 (22.85) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

1.8 (0.07) |

9.5 (0.37) |

20.2 (0.80) |

67.5 (2.66) |

100.1 (3.94) |

93.2 (3.67) |

73.8 (2.91) |

56.9 (2.24) |

40.3 (1.59) |

9.2 (0.36) |

1.0 (0.04) |

473.4 (18.64) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 22.2 (8.7) |

12.6 (5.0) |

12.1 (4.8) |

10.7 (4.2) |

1.7 (0.7) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.0) |

5.6 (2.2) |

18.9 (7.4) |

23.2 (9.1) |

107.1 (42.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.9 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 10.9 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 10.9 | 10.3 | 9.5 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 111.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 10.7 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 10.9 | 10.3 | 8.3 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 75.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 8.9 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 5.9 | 8.0 | 38.1 |

| Source: Environment Canada[63] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]

As the economic centre of Southeastern Manitoba, service/retail industries employ the majority of the working population. Large manufacturing plants, especially those operated by Barkman, Bausch and Loewen Windows (which is also headquartered in Steinbach), create a significant number of jobs. Since the 1950s, Steinbach has been known as a centre for automobile sales, marketing itself as the "Automobile City". Steinbach has a diversity of jobs and industries within the community. Its rapid growth rate, combined with the lowest taxes in the province by mill rate, has made the community an increasingly popular place for both workers and employers.[64] This combination has helped many different mid-sized and large-sized businesses in manufacturing, transportation, agribusiness, pharmaceuticals, retail, and financial services such as the Steinbach Credit Union, to grow with the city.[64] As a result, the city of Steinbach now has the third-highest assessment value among cities in the province, trailing only Brandon and Winnipeg.[64]

Agriculture, the traditional industry in the region, continues to play a significant role in Steinbach's economy as well. The agricultural industry in the area is notable for many of the large commercial pig and poultry farming operations.[65] Aside from intensive pig and chicken barns there are numerous small, family, dairy farms that dot the area.[66] Crops grown on the fertile farmland surrounding Steinbach primarily include canola, corn, alfalfa, as well as barley, soybeans, oats, and wheat.[66][67][68][69]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1946 | 1,071 | — |

| 1951 | 2,155 | +101.2% |

| 1961 | 3,739 | +73.5% |

| 1971 | 5,197 | +39.0% |

| 1981 | 6,676 | +28.5% |

| 1986 | 7,473 | +11.9% |

| 1991 | 8,213 | +9.9% |

| 1996 | 8,478 | +3.2% |

| 2001 | 9,227 | +8.8% |

| 2006 | 11,066 | +19.9% |

| 2011 | 13,524 | +22.2% |

| 2016 | 16,022 | +18.5% |

| 2021 | 17,806 | +11.1% |

| Source: [22][31][70][71] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Steinbach had a population of 17,806 living in 6,836 of its 7,092 total private dwellings, a change of 11.1% from its 2016 population of 16,022. With a land area of 37.56 km2 (14.50 sq mi), it had a population density of 474.1/km2 (1,227.8/sq mi) in 2021.[71] This places Steinbach as the third largest city in Manitoba. The average age of people in Steinbach is 37.8, below the provincial average of 39.2, while 52% of the population are female and 48% are male.[72]

A total of 30% of Steinbach residents claim German as their mother tongue, which includes both High German and Plautdietsch, while nearly 80% of those with a second language claim knowledge of a Germanic language.[73] As a whole, 39% of residents claim some mother tongue other than the official languages of French and English.[72] Steinbach has an immigrant population of 21.39% or about 2,890 people, which is slightly above the provincial average of 18.33%.[73]

The median after-tax household income in 2020 for Steinbach was $64,000, which is below the Manitoba provincial average of $69,000.[74]

Ethnicity

[edit]Approximately twenty-four per cent of Steinbach residents claim German ancestry, though this may include those from Germany itself or of Mennonite background, which would more accurately be described as Dutch.[75] In 2021 Canadian census, nearly 20 per cent of the community reported Mennonite ethnicity.

| Population | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| German | 4,285 | 24.38 |

| Mennonite | 3,505 | 19.94 |

| Russian | 2,235 | 12.71 |

| Canadian | 2,075 | 11.80 |

| Filipino | 1,455 | 8.27 |

| English | 1,415 | 8.05 |

| Ukrainian | 1,370 | 7.79 |

| French | 1,305 | 7.43 |

| Dutch | 1,240 | 7.05 |

| Scottish | 1,190 | 6.77 |

| Panethnic group | 2021[76] | 2016[77] | 2011[78] | 2006[79] | 2001[80] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European[a] | 13,055 | 74.28% | 12,670 | 81.56% | 11,460 | 86.92% | 9,880 | 91.06% | 8,410 | 93.13% |

| Indigenous | 1,755 | 9.99% | 1,055 | 6.79% | 655 | 4.97% | 530 | 4.88% | 360 | 3.99% |

| Southeast Asian[b] | 1,640 | 9.33% | 1,165 | 7.5% | 690 | 5.23% | 225 | 2.07% | 125 | 1.38% |

| South Asian | 515 | 2.93% | 155 | 1% | 130 | 0.99% | 110 | 1.01% | 30 | 0.33% |

| Latin American | 220 | 1.25% | 105 | 0.68% | 35 | 0.27% | 20 | 0.18% | 10 | 0.11% |

| African | 210 | 1.19% | 200 | 1.29% | 120 | 0.91% | 35 | 0.32% | 30 | 0.33% |

| East Asian[c] | 90 | 0.51% | 95 | 0.61% | 50 | 0.38% | 30 | 0.28% | 60 | 0.66% |

| Middle Eastern[d] | 10 | 0.06% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Other/multiracial[e] | 90 | 0.51% | 85 | 0.55% | 45 | 0.34% | 20 | 0.18% | 15 | 0.17% |

| Total responses | 17,575 | 98.7% | 15,535 | 96.96% | 13,185 | 97.49% | 10,850 | 98.05% | 9,030 | 97.86% |

| Total population | 17,806 | 100% | 16,022 | 100% | 13,524 | 100% | 11,066 | 100% | 9,227 | 100% |

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||

Religion

[edit]Census data from 2011 shows that 88.73% of Steinbach residents report a religious affiliation, which is above the provincial average of 73.51%.[81] Of those with a religious affiliation, 74.58% are Protestant, and 12.44% are Catholic.[81] Less than 1% belonged to either Buddhism, Islam, Judaism or Hinduism combined. In the total population surveyed, 11.27% claim no religious affiliation.[81]

Government

[edit]

Civic government

[edit]Steinbach is represented by six councillors and a mayor.[82] The city is a single-tier municipality, governed by a mayor-council system, the mayor and council are elected every four years. The current mayor is Earl Funk.

Prior to incorporation as a town in 1946, Steinbach was part of the East Reserve and later Rural Municipality of Hanover. The entire area was led by an Oberschulz, while the village of Steinbach was governed by a Schulz (mayor) and Schultebott (council).[8] Steinbach's first schulz was Johann Reimer, while Steinbach's longest-serving schulz was Johan G. Barkman (son of Rev. Jakob Barkman), who served as schulz for 25 years.[8]

Federal and provincial representation

[edit]| Year | Liberal | Conservative | New Democratic | Green | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 11% | 837 | 53% | 3,862 | 9% | 666 | 2% | 161 | |

| 2019 | 8% | 574 | 76% | 5,437 | 8% | 604 | 6% | 412 | |

| Year | PC | New Democratic | Liberal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 80% | 4,036 | 9% | 435 | 6% | 287 | |

| 2016 | 87% | 3,740 | 6% | 259 | 7% | 301 | |

Currently, the city is represented federally by the Conservative Party of Canada and provincially by the Progressive Conservative Party of Manitoba. The city and surrounding area comprise the provincial riding of Steinbach, which has been represented in the Manitoba Legislative Assembly by MLA Kelvin Goertzen since 2003. In federal politics, the city is part of the Provencher riding, which has been represented by MP Ted Falk since 2013.

Infrastructure and public services

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Access

[edit]

Steinbach is unusual in that there are no railways or rivers passing through town, so transportation to and from Steinbach has always been by road. The city is located approximately 50 kilometers southeast of Winnipeg, in a direct line. There are two principal highways serving the city, Provincial Trunk Highways (PTH) 12 and 52, which intersect at downtown Steinbach. Travelers coming from Winnipeg can take the Trans-Canada Highway (PTH 1) east for 40 kilometers, turning south at PTH 12 and continuing for 20 kilometers. This entire route consists of four-lane limited-access highways. Alternatively, travelers can also take PTH 59 south from Winnipeg and then take PTH 52 east to Steinbach. PTH 12 south from Steinbach is single-lane and ends at the American border at Sprague. Steinbach is situated on an alternate route between Winnipeg and Thunder Bay, Ontario which is named MOM's Way.

Airports

[edit]The City of Steinbach owns and maintains Steinbach Airport, a federally registered aerodrome located 1 nautical mile (1.9 km; 1.2 mi) north of the city. The runway is 3,000 by 75 ft (914 by 23 m) and has an asphalt surface.[85] The runway is serviced with lighting and a beacon for night-time use. Fuel and servicing are available on site and are provided through the Steinbach Flying Club. The airport also features aircraft tie-downs, a heated lounge building and restroom facilities.

Additionally, Harv's Air Service operates Steinbach (South) Airport, a private aerodrome 2 nautical miles (3.7 km; 2.3 mi) south of the city. The main runway is 3,112 by 100 ft (949 by 30 m) and has an asphalt and turf surface. An additional runway measuring 1,834 by 100 ft (559 by 30 m) intersects the main runway to the north.[85]

Health

[edit]Health for the city and surrounding area is governed by Southern Health-Santé Sud. Acute care and emergency services are provided by the Bethesda Regional Health Centre.

Utilities

[edit]The water supply for Steinbach comes from three wells drilled into a limestone aquifer in K.R. Barkman Park and two wells were also recently established by Park Road West and Keating Road.[86] It is then sent to a water treatment plant that was upgraded in 2006.[87] Treated water storage is located in a 47 m (154 ft) tall elevated water tower that was built in 1972 and an additional underground water storage unit in 1999; combined they provide the community with 9,800,000 L (2,200,000 imp gal; 2,600,000 US gal) of treated water.[87] A new secondary water treatment plant was constructed in 2019 at a cost of $11.3 million to meeting the growing city's demand for water.[88] As of 2019, it was the city's largest infrastructure project in its history.[88]

Education

[edit]

Steinbach is part of the Hanover School Division, which is one of the 37 school divisions in Manitoba. This is also the largest school division outside of the city of Winnipeg.[89] The school system in Manitoba is dictated by the province through the Manitoba Public Schools Act. Public schools follow a provincially mandated curriculum in either French or English.

The schools in Steinbach consist of three Early Years Elementary Schools: Woodlawn, Southwood and Elmdale which provide education from kindergarten through Grade 4. Grades 5 through 8 are currently provided by two newly formed Middle Schools: Stonybrook Middle School (formerly Steinbach Junior High School) and Clearspring Middle School (established 2012).[90] Steinbach Regional Secondary School is a large public high school providing Grades 9 through 12 education for Steinbach and the surrounding region; it is the second largest school in Manitoba. Steinbach Christian Schools, a private school, offers all grades (Kindergarten – Grade 12).

Steinbach is home to the evangelical Anabaptist college Steinbach Bible College,[91] which shares a campus with Steinbach Christian Schools. It also has a post-secondary learning campus called Eastman Education Centre, which offers courses from Red River College, University of Winnipeg, Assiniboine Community College and Providence University College.[92]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Opening in 1967, and undergoing numerous expansions since then, the Mennonite Heritage Village is Steinbach's foremost cultural facility and tourist attraction. It provides a glimpse at the life of Mennonite settlers through a reconstructed street village and interpretive displays. Its Dutch windmill, which was rebuilt (with help from Dutch millwrights) after the 1972 replica was destroyed by arson in 2000, is a recognized symbol of the city.[93]

The Mennonite Heritage Village's Pioneer Days festival, and the accompanying parade, has existed each August since the 1970s. Steinbach's 'Summer in the City' festival is held on Main Street each June. The Steinbach Arts Council has showcased Steinbach arts and culture, of various types, since the 1980s.

The Johann G. Barkman Heritage Walkway, stretching along Elmdale Drive, is named after an early long-time mayor, and features plaques and other historic markers documenting the life of early Steinbach along the, now dry, Steinbach Creek.

Steinbach has had a public library since 1973, although serious efforts to establish a regional library began in 1968 when Mary Barkman organized a Friends of the Library group. In 1997, the library moved into its own newly constructed building and was renamed Jake Epp Library.[94] Jake Epp, former MP of Provencher, had appointed the very first Library Board in 1973. Mary Barkman, a key figure in the founding of the Library, was also honored at the opening ceremony. After his death in 1998, the library revealed a plaque and reading garden honouring former local teacher Melvin Toews, father of author Miriam Toews and subject of her book Swing Low: A Life. A major library expansion was completed in 2012.[95][96]

Steinbach is known for having a significant place in the world of Mennonite literature.[97][98][99] Arnold Dyck was the editor of the German-language Steinbach Post in the early 20th century and the first writer to use Plautdietsch as a written language. In the 1970s and 80s came the work of poet Patrick Friesen, author of The Shunning and many other works, novelist and literary critic Al Reimer, author of My Harp is Turned to Mourning and the Kleindarp stories, and Roy Vogt, founder of the Mennonite Mirror and the Mennonite Literary Society.[100] Beginning in the 1990s, Steinbach's most well-known author Miriam Toews has written numerous award-winning and bestselling novels, some of which are set in Steinbach. Her non-fiction book Swing Low: A Life is set in Steinbach, while her bestselling novels A Complicated Kindness and All My Puny Sorrows, as well as the film adaptation of the book, are set in the fictional East Village, widely regarded to be based on her hometown.[24] Fight Night, inspired by Toews's mother Elvira, also alludes to Steinbach.[101] In 2016, Steinbach writer Andrew Unger started The Unger Review (formerly The Daily Bonnet), a website that publishes satirical Mennonite news stories,[102] and published the novel Once Removed in 2020, which draws on fictional elements of Steinbach.[103] Steinbach has also been home to novelist Byron Rempel, memoirist Lynette Loeppky, poets Lynnette D'anna, Luann Hiebert, and Audrey Poetker, as well as historians Royden Loewen and Delbert Plett, among others. In 2024, a historic plaque was unveiled in front of Miriam Toews's teenage home in Steinbach.[104]

Regional cuisine unique to Steinbach would include various Mennonite dishes such as vereniki, farmer sausage, sunflower seeds, yerba mate and roll kuchen.[105][106][107][108] Mennonite homes frequently serve a light lunch on Sundays called faspa consisting of deli meats, cheese curds, pickles, buns, and dessert such as plautz.[109][110][111] These items can be found at restaurants that specialize in Mennonite food, such as MJ's Kafe and the Livery Barn Restaurant (at the Mennonite Heritage Village), as well as in local homes, community and church events, and on the menu of many other local restaurants.[112][113]

In 2018, Steinbach became a sister city with Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, which is near where all of Steinbach's pioneering families immigrated from in the 1870s.[114]

In 2021, the Public Brewhouse and Gallery opened on Main Street in Steinbach, the first brewery to open in the former dry community, and the first privately run art gallery in the southeast.[115][116]

Steinbach is the headquarters of both the Evangelical Mennonite Conference, formerly known as the Kleine Gemeinde, and the Christian Mennonite Conference, formerly known as Chortitzer Mennonite Conference.[117] The city has among the most churches per capita of any city in Canada, at one for every 500 people.[118] Steinbach is home to at least 22 churches and while many of the smaller churches are Mennonite, the majority of Steinbach's current population no longer attend a Mennonite church, and the largest churches in the city, such as the Emmanuel Evangelical Free Church, Southland Community Church, and Crossview Church, are either non-denominational or evangelical and are not part of Mennonite denominations.[119]

Media

[edit]Currently, Steinbach's oldest media outlet is The Carillon, an award-winning weekly newspaper founded in 1946 by Eugene Derksen that covers the news of Southeastern Manitoba. Steinbach also has three radio stations run by Golden West Broadcasting: AM 1250 is an easy listening station, Mix 96.7 FM plays current pop hits, and CJXR-FM is a country station. Steinbach is also home to Die Mennonitische Post, one of the last remaining German-language newspapers in North America.[120] Started by Jacob S. Friesen in 1913 and taken over by Arnold Dyck in 1924, Steinbach was also home to the German-language Steinbach Post for many decades.[121]

Sports and recreation

[edit]Baseball

[edit]First organizer by local banker T.G. Smith, Steinbach has had recreational baseball since 1955.[122] Steinbach is home to a number of baseball diamonds, most notably at the A.D. Penner Park. The city is home to teams such as the Carillon Sultans.[123]

Canadian football

[edit]The Eastman Raiders football club, based in Steinbach, was formed in 1991. There are now over 260 athletes, ranging in age from 7 to 22, playing in the Raiders program.[124] In 2009, the Eastman Raiders midget team captured their first championship with a 20–9 victory over the St Vital Mustangs.[125]

The most notable football player from Steinbach is star CFL running back Andrew Harris.

Curling

[edit]The Steinbach Curling Club opened in October 2014 and is located adjacent to the T.G. Smith Centre. It has five sheets and hosts a variety of different leagues, including a successful junior program.[126] The current rink replaced the previous one that was built in 1948 and located across the street.[127]

A number of Steinbach curlers have gone on to have success at the provincial and national level, most notably Brier-winners Vic Peters and Chris Neufeld. Steinbach has also hosted two Safeway Select Provincial Men's Curling Championships (2006 and 2010).

Golf

[edit]

The Steinbach Fly-in Golf Club is an 18-hole golf course adjacent to the local airport.[128] Quarry Oaks Golf and Country Club, Girouxsalem Golf and Country Club, and Ridgewood South Golf Course are just outside the city.[129]

Ice hockey

[edit]Steinbach is home to the Manitoba Junior Hockey League's Steinbach Pistons. The Pistons have won three Turnbull Cups (2012–13, 2017–18, 2022–23) and one ANAVET Cup (2017–18). The Pistons also participated in the 2013 Western Canada Cup, 2018 Royal Bank Cup and 2023 Centennial Cup.

The Steinbach Huskies senior hockey club have been a fixture in the local hockey scene since the 1920s. The Junior Huskies are eight-time champions of the Hanover Tache Junior Hockey League. The Huskies qualified for the 1979 Allan Cup finals as Western Canadian champions, but lost the best-of-seven series 4–1. Steinbach's minor hockey teams are known as the Steinbach Millers.

Steinbach has hosted the Allan Cup, Canada's senior 'AAA' hockey championship, twice in 2009 and 2016. The 2009 Allan Cup featured two Steinbach-based teams, the host Steinbach North Stars and the Manitoba champion South East Prairie Thunder competing in the tournament. The Prairie Thunder advanced as far as the championship game, which was broadcast nationally on TSN, but lost in double overtime. Three years later, the Prairie Thunder captured their first ever national title at the 2012 Allan Cup. The 2016 Allan Cup was also held in Steinbach, hosted by the Prairie Thunder.[130]

Notable professional hockey players from Steinbach include Jon Barkman, Ken Block, Paul Dyck, Dale Krentz, Jeff Penner, Sean Tallaire, and Ian White, as well as NHL coach Ralph Krueger.

Soccer

[edit]Steinbach is home to a number of soccer teams, including the men's Hanover Kickers, who play in Manitoba's Premier League Two, the Hanover Strikers who play in Major League Two of Manitoba Major Soccer League, and the Hanover Hype playing in the Winnipeg Women's Soccer League. The city also has a Futsal league that operates during the winter.[131] The 40 acre Steinbach Soccer Park, opened in 2009, contains 5 full-size soccer pitches.[132]

Swimming

[edit]The Steinbach Aquatic Center adjacent to nearby A.D. Penner Park, opened in 2002 and contains an indoor pool with waterslide as well as an outdoor pool open seasonally.[133]

Notable people

[edit]Actors

[edit]- Scott Bairstow, actor[134]

- Allison Hossack, actress[135]

Athletes

[edit]- Jon Barkman, former professional hockey player

- Ken Block, former professional hockey player

- Paul Dyck, former professional hockey player

- Andrew Harris, Canadian football player[136]

- Dale Krentz, former professional hockey player

- Eric Loeppky, volleyball

- Chris Neufeld, curler, Brier champion[137]

- Denni Neufeld, curler

- Jeff Penner, former professional hockey player

- Vic Peters, curler, Brier champion[137]

- Michelle Sawatzky-Koop, Olympian, volleyball

- Sean Tallaire, former professional hockey player[138]

- Ian White, former professional hockey player

Musicians

[edit]- Julian Austin, country musician

- Matt Epp, singer-songwriter

- The Pets, rock band[139]

- Danny Plett, Contemporary Christian musician

- Royal Canoe, indie rock band

- Shingoose, Ojibwa folk singer

- The Undecided, pop-punk band

- The Waking Eyes, alternative rock band

Politicians

[edit]- Robert Banman, former MLA, provincial cabinet minister

- Leonard Barkman, former mayor and MLA[140]

- Henry Braun, former mayor of Abbotsford, British Columbia

- Albert Driedger, former MLA and cabinet minister

- Jake Epp, former MP and federal cabinet minister[141]

- Ted Falk, MP

- Kelvin Goertzen, MLA and 23rd Premier of Manitoba[142]

- Russ Hiebert, MP[143]

- Judy Klassen, MLA

- Helmut Pankratz, mayor and MLA

- A.D. Penner, mayor

- Jim Penner, MLA

- Vic Toews, politician

Writers

[edit]- Lynnette D'anna, writer

- MaryLou Driedger, Young Adult fiction author

- Arnold Dyck, writer

- Patrick Friesen, poet[144]

- Lynette Loeppky, writer

- Royden Loewen, historian

- Delbert Plett, lawyer and historian

- Audrey Poetker, poet

- Al Reimer, writer

- Byron Rempel, writer

- Wayne Tefs, writer, co-founder of Turnstone Press

- Miriam Toews, novelist[145]

- Andrew Unger, writer

- Roy Vogt, writer

Other

[edit]- John Martin Crawford, serial killer

- Ralph Krueger, former ice hockey head coach and soccer executive

- Raymond Loewen, businessman as depicted in the 2023 film The Burial

- Peter Olfert, labour leader

- Robert L. Peters, graphic designer

- Jeremy St. Louis, broadcaster

- Erich Vogt, physicist

Notes

[edit]- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

References

[edit]- ^ "Steinbach". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ a b "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Steinbach". Census Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ "Data table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population – Steinbach, City". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Steinbach Demographics". Census Profile, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Trading Area, Business & Industry

- ^ "Data table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population – Steinbach, City". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ a b Joe Friesen (10 May 2012). "How immigrants affect the economy: Weighing the benefits and costs". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Friesen, Ralph (September 2009). Between Earth and Sky: Steinbach, The First 50 Years. Derksen Printers.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ralph Friesen (2019). Dad, God, and Me. FriesenPress.

- ^ a b Ernest Braun and Glen Klassen (2015). Historical Atlas of the East Reserve. Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Steinbach History 1874 - 1990". 1 May 1990. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ a b Francis, E.K. (1955). In Search of Utopia. D.W. Friesens and Sons.

- ^ "Jakob M. Barkman". GAMEO. Retrieved 17 February 2002.

- ^ "History of Steinbach". Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ a b Abe Warkentin (1971). Reflections on our heritage. Derksen Printers.

- ^ Friesen, Ralph (December 2018). Revive Us Again: A Brief History of Revivalism in Steinbach. Preservings.

- ^ Erin Unger (11 March 2020). "Local History and Coronavirus: 5 Questions with Glen Klassen". Mennotoba. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Wesley Peters. "Why Mennonite Death Rate Was Double The Average During Spanish Flu". Pembina Valley Online. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ a b Epp, Frank H. (1962). Mennonite Exodus. D.W. Friesen and Sons.

- ^ Hildegard Adrian. "How McKenzie Road Got Its Name" (PDF). Preservings. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ della Cava, Marco (13 October 2023). "Fact checking 'The Burial': How accurate is Jamie Foxx, Tommy Lee Jones' courtroom drama?". USA TODAY. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "City of Steinbach". The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Reflections on our Heritage" (PDF). Derksen Printers Ltd. 1971. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ a b Magdalene Redekop (2020). Making Believe: Questions About Mennonites and Art. University of Manitoba Press.

- ^ "Daily Book Review: Inside the life of Canada's rock-star criminal." Globe & Mail, July 7, 2011. Retrieved: September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Politics". The Mennonite Encyclopedia. Herald Press. 1990.

- ^ "Clearspring Centre 40th Anniversary". The Carillon. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Cancellation of rock concert". The Carillon News. 3 November 1982.

- ^ Miriam Toews (2004). A Complicated Kindness.

- ^ Aileen Friesen. Unraveling the Russian Mennonite Baptist Identity in Western Siberia. University of Winnipeg.

- ^ a b c Manitoba – City Population – Cities, Towns & Provinces – Statistics & Map

- ^ a b "How dry is Steinbach to be?". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 18 February 2002.

- ^ "Arrests made in 10 year old windmill arson". CBC. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Froese, Ian (30 March 2016). "Trailblazers highlight MHV year". Winnipeg Free Press. The Carillon. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Caldwell, Rebecca (17 November 2004). "Toews, Dallaire win G-G awards". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "And The Winner Is A Complicated Kindness". cbc.ca. 22 April 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Geoff Kirbyson (9 February 2012). "Steinbach booms to No. 3 city in province". Winnipeg Free Press.

- ^ Daryl Braun (11 May 2012). "Steinbach Seen As A Model For Canada". SteinbachOnline.

- ^ The Public Schools Amendment Act (Safe and Inclusive Schools)

- ^ CBC News (13 September 2013). "Bill 18 passes in Manitoba legislature". CBC News. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ James Turner (9 July 2016). "First Pride march in Steinbach, Manitoba draws thousands". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Thousands take part in the 1st Pride parade in Steinbach, Man". CBC News. 9 July 2016.

- ^ Alexandra Paul (9 July 2016). "Thousands welcome Pride to Bible belt". Winnipeg Free Press.

- ^ Ian Froese (9 July 2016). "Thousands take in Steinbach's first Pride". The Carillon.

- ^ Shannon Dueck (25 June 2015). "Annexation A "Win-Win Situation"". Steinbach Online. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Steinbach-area restaurants closing to avoid 'domino-effect' of COVID-19 cases". CBC Manitoba. 3 August 2020.

- ^ "Woman dies following COVID-19 outbreak at Steinbach care home while Manitoba sees 25 new cases". CBC Manitoba. 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Covid infection rate soaring in Steinbach". CTV News. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Carol Sanders (13 November 2020). "Situation at Steinbach hospital 'concerning'". Winnipeg Free Press.

- ^ Marina von Stackelberg (13 November 2020). "'Completely overwhelming': Steinbach ER at capacity treating COVID-19 patients, nurse says". CBC Manitoba.

- ^ "Census shows 21 per cent of Steinbach residents are immigrants". Steinbachonline.com. 26 October 2022.

- ^ a b Steinbach votes on alcohol – again – Prohibition sparked seven referendums. Winnipeg Free Press, 17 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "It's a Steinbach compromise". Winnipeg Free Press (Historic Article). 25 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Steinbach council approves liquor store. CBC News online, 20 February 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "New liquor mart opens tomorrow", Manitoba Liquor Control Commission, News Release, 19 March 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Steinbach residents vote to loosen liquor laws. Winnipeg Free Press, 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011. Archived 30 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Steinbach residents vote to get wetter". Carillon News. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Steinbach voters cast their ballots in favour of liquor in referendum. Winnipeg Free Press, 26 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Schellenberg, Trev (24 October 2018). "Steinbach and Stuartburn Say No To Retail Cannabis". SteinbachOnline.

- ^ Karen Loewen (24 September 2014). "Interesting Nearby Destinations Cont'd – The Afternoon". Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ World Lake Database. "Lake Winnipeg". Archived from the original on 10 February 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ^ "Steinbach, Manitoba Koppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Steinbach". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010 Station Data. Environment Canada. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Bob Armstrong (March 2007). "A Growing Rural Powerhouse". Manitoba Business Magazine.

- ^ "Stop the Hogs - Manitoba". Stop the Hogs. 12 September 2003. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ a b Chris Teetaert (3 July 2010). "Rain And Heat Impact Southeast Crops". SteinbachOnline. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "Thousands Of Acres Of Winter Wheat Spoiled". SteinbachOnline. 19 May 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "Some Corn Being Harvested". SteinbachOnline. 24 November 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ Chris Teetaert (31 March 2010). "Heat Helping Some Crops". SteinbachOnline. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ City of Steinbach- Official Community Plan (Sept. 2008)

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), Manitoba". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ a b "2006 Census Profile - Steinbach, CY" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Steinbach household income lags behind provincial average". Steinbach Online. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ "Mennonites". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (26 October 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (27 October 2021). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (27 November 2015). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (20 August 2019). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2 July 2019). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "2011 National Household Survey: Data Tables - Religion". Statistics Canada, 2011 National Household Survey. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "City of Steinbach – Mayor & Council". City of Steinbach. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ "Official Voting Results Raw Data (poll by poll results in Steinbach)". Elections Canada. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ "Official Voting Results by polling station (poll by poll results in Steinbach)". Elections Manitoba. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 16 July 2020 to 0901Z 10 September 2020.

- ^ Lexi Olifirowich (2 May 2023). "City's waterworks manager shares surprising stats on Steinbach's water". Steinbach Online.

- ^ a b "Bylaw No. 1983" (PDF). City of Steinbach. Public Utilities Board Manitoba. 10 September 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b Daryl Brown (13 May 2019). "New Steinbach Water Plant Almost Finished". Steinbach Online. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "About Us". Hanover School Division. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ "Schools of the Future". Hanover School Division. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ^ "History". Steinbach Bible College. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "About Us". Eastman Education Centre. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ "Charges laid in decade-old windmill arson". Winnipeg Free Press. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ History of the Jake Epp Library Archived 24 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Jake Epp Library Expansion Archived 31 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. City of Steinbach website. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Library Expansion News Archived 11 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Manitoba's literary locales". Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Mennonite Studies". Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Steinbach ... the Literary City". CBC Radio. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ James Urry (2006). Mennonites Peoplehood and Politics. University of Manitoba Press.

- ^ Lederman, Marsha (20 August 2021). "Miriam Toews new novel pays tribute to her mother". Globe and Mail.

- ^ Schwartz, Alexandra (25 March 2019). "A Beloved Canadian Novelist Reckons with Her Mennonite Past". The New Yorker. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Emily Unrau-Poetker (22 September 2020). "Andrew Unger – Once Removed". The Manitoban. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Miriam Toews' teenage house honoured with plaque". The Carillon. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Steinbach museum exhibit looks at the Mennonite menu". Manitoba Co-operator. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Redekop, Bill (8 August 2015). "Steinbach museum explores food traditions, and serves it up too". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Meat that matters". The Western Producer. 28 January 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Andrew J. Bergman (6 November 2017). "The Mennonite Obsession with Yerba Mate". Mate Over Matter. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Faspa". Steinbach Bible College. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Livery Barn Restaurant". Eastman Tourism. 3 September 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Brittany Penner. "I'm Metis, but grew up white in an adopted family". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Schwartz, Alexandra (25 March 2019). "A Beloved Canadian Novelist Reckons with Her Mennonite Past". The New Yorker. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "14 road-trip worthy restaurants you absolutely have to try this summer". Travel Manitoba. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Steinbach Becomes Twin City With Zaporizhia". Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "City Council Approves Variance for Micro-Brewery and Art Gallery". steinbachonline.com. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ "Brewery Opens in Formerly Dry Town". Mennotoba. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ "Evangelical Mennonite Conference". Evangelical Mennonite Conference. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Religious revival:Steinbach's already large Southland Church set to double". Winnipeg Free Press. 24 September 2011.

- ^ "The 'real Steinbach' isn't as Mennonite as it once was". CBC News. 23 March 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Die Mennonitische Post celebrates 40th anniversary". 23 June 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Cornelius Krahn (1959). Steinbach Post. The Mennonite Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Manitoba Baseball Hall of Fame pays tribute to T.G. Smith". The Carillon News.

- ^ "Carillon Sultans won 15U AAA Provincials". Steinbach Online.

- ^ "High school football league expands by 3". Winnipeg Free Press. 3 March 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Midget Football League of Manitoba – Midget Football League of Manitoba

- ^ Leagues, Schedules & Fees - Steinbach Curling Club

- ^ "Curlers take in new Steinbach Curling Club". The Carillon. 27 October 2014.

- ^ Sandilands Ski Club (go to Trail Conditions). Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ "Steinbach, Manitoba Golf Guide". NBC Golf Pass. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ "2016 Allan Cup Confirmed In Steinbach". 5 September 2014.

- ^ Southeast Futsal page

- ^ "Soccer". City of Steinbach.

- ^ "Steinbach Aquatic Centre Marks Ten Years". Steinbach Online.

- ^ "Scott Bairstow". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "Allison Hossack". Hallmark Channel. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "Winnipeg's Andrew Harris signs extension with B.C. Lions". MyToba.ca. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Gimli Family Rocks". The Interlake Spectator. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "TALLAIRE SEAN MICHAEL - Obituaries - Passages". passages.winnipegfreepress.com.

- ^ Last.fm – The Pets. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Leonard Barkman". The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "Arthur Jacob "Jake" Epp". Jake Epp Library. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ "Kelvin Goertzen to become Manitoba's next premier". CTV. 31 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "Meet our Candidates". Conservative Party of Canada. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Patrick Friesen Profile". Manitoba Writer Index. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Miriam Toews Manitoba Author Publication Index Archived 10 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine